In a tense climate where market actors are holding their breath before every inflation data print or Fed/ECB meeting, distressed fiscal levers in the US, and uncertainty flooding the minds and models of forecasters, there is a persistent question mark over the soundness of the financial and banking sector worldwide.

This article will shed light on the root causes of said turmoil while delivering an assessment of the sector’s health and discussing the fitness of the regulatory framework organizing the sector’s activities.

Multiplicity of tailwinds : difficult financing conditions, growth slowdown and heightened risks

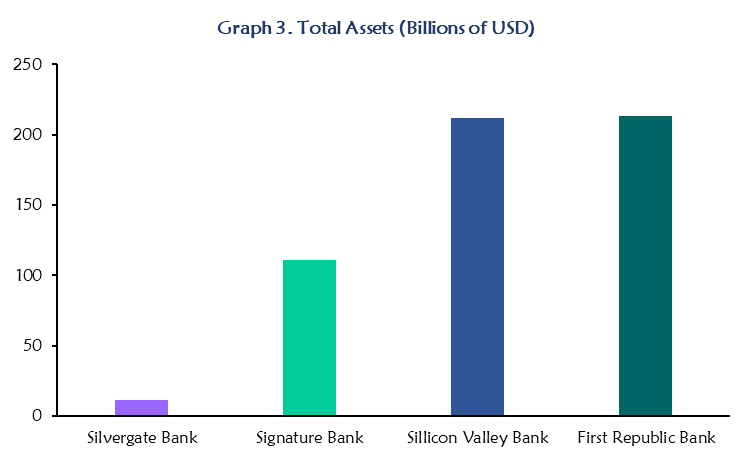

Silvergate Bank, Signature Bank, Sillicon Valley Bank, Crédit Suisse and First Republic Bank, those are the unfortunate headlining stars of what is now coined as 2023 banking crisis. Their fall is a result of a combination of factors degrading the most valuable asset in the financial system, i.e. trust.

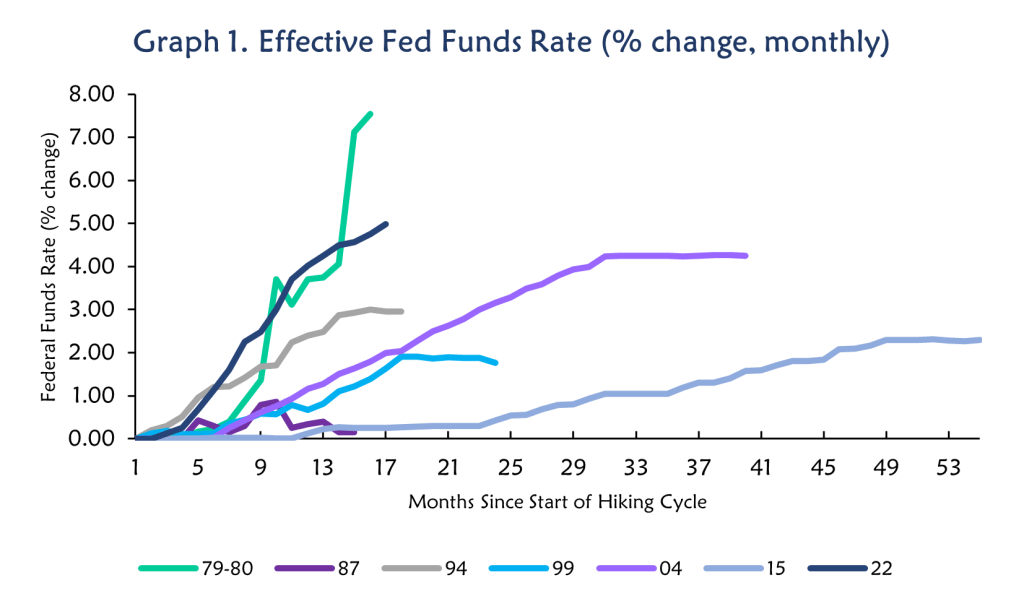

To bring some context, one must simply recall that the world is witnessing the fastest rate hike trend of the past 40 years, putting a hard strain on the banking sector financing conditions. Additionally, earlier this year, US Treasury yields were at their highest in 22 years, causing a fall in US bonds prices, combined with decreasing US stock prices, both by 10%; a situation markets have not observed for the past 150 years. By all metrics, the maturity transformation function of the banking system is getting more complex.

On top of that, freshly released World Bank Global Economic Prospects (January 2024) show divergent growth figures forecasts across world economic regions, hence with a predominant slowdown and global growth for 2023 posting at 2.6%, down from 3% in 2022. The growth slowdown is expected to put a drag on credit growth, therefore lowering banks’ sources of revenues.

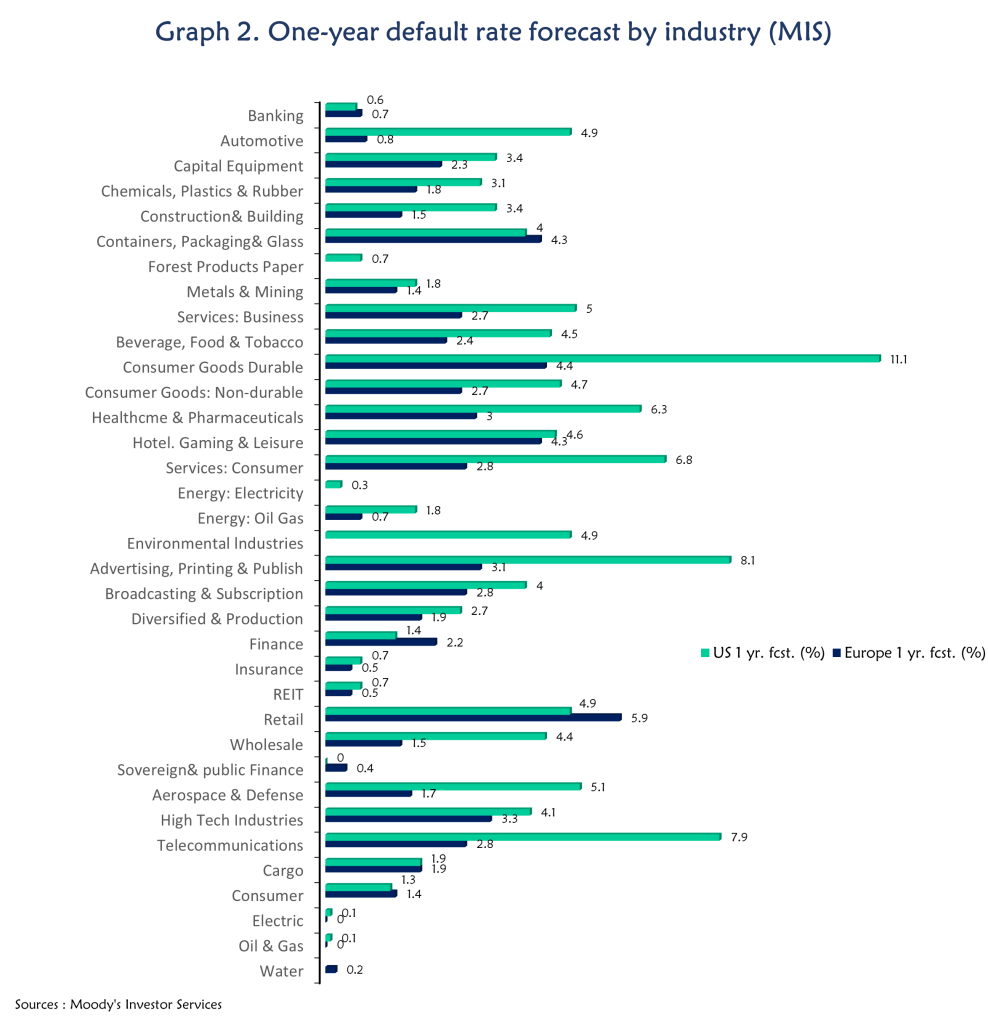

Besides, the banking sector is facing heightened risks as the economic outlook challenges the profitability of its clients. In fact, credit risk is on the rise, as evidenced in the below chart for the US and Europe. Industries such as automotive, business services, durable consumer goods, advertising or even telecommunications have seen a spike in their one-year forecasted default rate, especially in the US. Other risks such as FX risk due to geoeconomic transformation or market risk caused by record breaking volatility and markets over-sensitiveness may arise.

The paradox : failing outliers, rock solid banking system

Throughout the crisis, regulators stuck to the narrative of a solid banking system, arguing that failing banks were more of outliers struggling with isolated governance issues and microprudential shortcomings, while the majority of other banks had in fact, despite the challenging conjuncture, a sound standing.

This narrative is to a certain extent grounded in reality, with hard facts supporting the regulators’ view.

In fact, the four concerned US banks and Crédit Suisse featured characteristics that were prone to weaken their solvability. Starting with the US banks, they all pertained to the class of relatively small regional banks, with balance sheet sizes not exceeding the USD 250 billion threshold, thus, following a 2019 US regulatory decision, being exempt from stress testing exercises and specific, timely additional capital requirements.

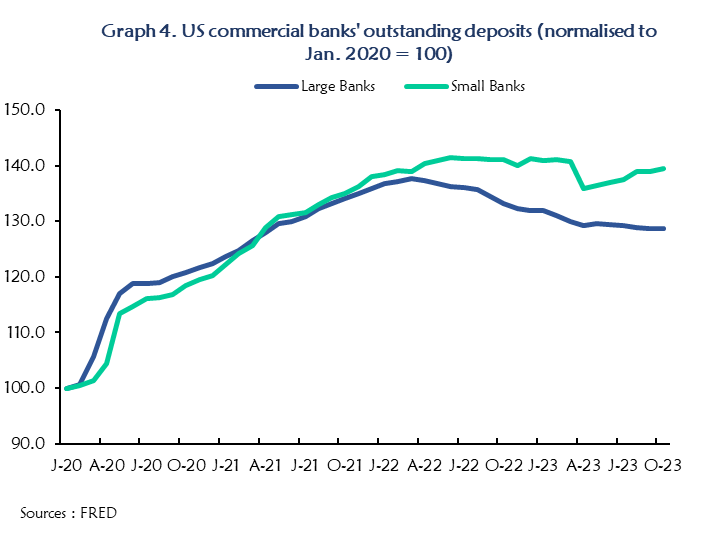

Additionally, small US regional banks witnessed a more pronounced cyclicality of deposits, with a sustained rise in deposit levels starting Q4 2021, while large banks observed mild but steady withdrawals. In contrast, the fall in deposits during 2023 spring turmoil was much visible for small US banks.

This tends to confirm what many scholars has described as « bank walks », a trend influencing the fluctuation of commercial banks’ deposits where digitisation and embedded brokerage platforms, over time, reduces the assumed stickiness of said deposits.

Moreover, some of the concerned US banks presented a flawed, or, at best, risky business models. In fact, most SVB and Signature Bank clients and depositors were concentrated in highly volatile sectors, respectively, tech and cryptos. They also overly relied on uninsured deposits for their financing. For both banks, those uninsured deposits represented more than 90% of their total deposits. An additional vulnerability was in sight, the concentration of these deposits in a small number of clients. In fact, for SVB, the top ten depositors alone accounted for USD 13 billion of the USD 173 billion in total deposits at the end of 2022.

On the asset side of the balance sheet, these banks were covering short-term financing needs with long-term investments. By the end of 2022, 57% of SVB’s assets consisted of fixed-income securities such as Treasuries and agency mortgage-backed securities (MBS). This high exposure to interest-sensitive assets should have inspired a cautious and more active risk management behaviour from the bank’s leadership. Instead, SVB managers unwound their meagre interest rate hedges and booked the gains as income. Some media reports on some senior managers of SVB selling large part of their equity in the bank few days before the bankruptcy points to a management that has apparently desperately engaged in a gamble for redemption, highlighting the major still predominant moral hazard in bank’s prudential matters.

Crédit Suisse, in turn, is incomparable both in size and in circumstances to the four other failing US banks. Crédit Suisse total assets as of end of 2022 were at roughly USD 243 billion, but most importantly, it had USD 1.4 trillion of assets under management (AUM). The troubles dated back to 2019 and spying allegations that led the then CEO Tidjane Thiam to resign in early 2020. Sizeable losses stemming from the failures of Greensill and Archegos funds in 2021, and the stated bank’s unsuccessful handling of prudential affairs in relationship with the two funds, further aggravated the situation. The ailing giant was also found guilty in a cocaine cash laundering case. On top of that, senior management was subject to high turnover and never achieved to stop the bank’s shares race to the bottom. The shockwave of SVB reinforced markets doubts on Crédit Suisse struggles with liquidity and capital and precipitated the end of the 167 years old Swiss bank.

Therefore, the US banks and Crédit Suisse appears in this narrative as plagued with specific frailties, especially that the last communicated figures tend to confirm the sound standing of the remainder of the banking systems.

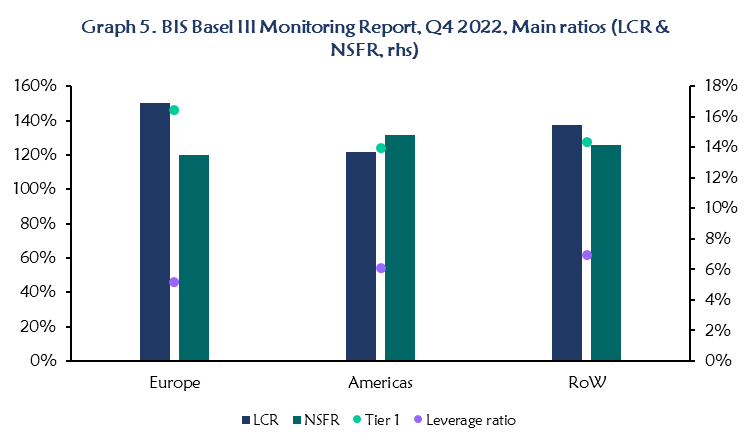

A BIS Basel III monitoring report, tracking the standing at the end of 2022 of 77 banks over the world, on different indicators and ratios shows a relatively reassuring picture of the global banking landscape.

European banks keep an edge in the soundness of their capitalization, with observed banks Tier 1 capital ratio printing at 16.44% at the end of 2022, while Americas and the Rest of the World present ratios of 13.98% and 14.33%, respectively.

However, the trend reverses when comparing leverage ratios, with European banks showing a lower level (5.14%) than other regions (6.06% for Americas and 6.94% for RoW), pointing to either a low riskiness of assets or more optimized RWA computation.

As for liquidity, indicators are also describing a rather positive and sound standing of global banks with figures above the minimum 100% thresholds for both short term Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and long term Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR).

Other reports and data communicated by EU or US regulators and supervisors convey the same message of stability and soundness of the banking system.

The alternative story : a tale of uninsured deposits, unrealised losses and moral hazard

Alternatively, another discourse has emerged ex post the crisis highlighting a set of structural trends that has weakened the structural standing of the banking system, predominantly in the US, but also in other parts of the world.

In fact, both US and Swiss regulators provided a swift response to tame a possible banking panic, as there were some motives of concerns about the safety of the banking system as a whole. In the US, Treasury Secretary and the Fed pushed the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to invoke the « systemic risk » exception to protect all deposits, including uninsured ones, at both SVB and First Republic. Following the same logic, through her statements, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen left the strong impression that depositors at other banks would be similarly protected. In Switzerland, the Swiss Central Bank provided significant amounts of liquidity to Crédit Suisse, to the tone of USD 54 billion, in a last attempt to save the banking giant, before it orchestrated its takeover by the country’s other giant, UBS, for USD 3 billion, as a measure to contain possible spillovers.

As previously mentioned, looking at structural trends in the US, a general observation of a banking system increasingly exposed to risk on the asset side and depending of volatile liabilities to fund it starts to take shape. Indeed, the share of uninsured deposits in total deposits neared the heights of 50% during the period of QE and ZLB concomitant to the COVID shock and fell to 44% in Q1 2023. Simultaneously, quarterly change in uninsured deposits spiked to the levels of USD 900 billion inflows to fall, in contrast, by almost USD 800 billion outflows.

On the asset side, the normalisation of monetary policy unleashed unprecedented consequences of interest rate risk on US banking system balance sheets. In 2017-19 monetary tightening, unrealised losses on banks’ securities peaked at less than USD 85 billion. In Q3 2022, those losses were eight times larger, printing at almost USD 700 billion.

Today, the storm has calmed down, however, it might not be over yet. With the previously described challenging environment and new risks uprise, some new breaks might occur down the road. Banks are set to face a sizable challenge with the progressive and phased entry into force of Basel III endgame / Basel IV rules relative to capital requirements. Additionally, current liquidity regulatory framework, according to the G20 FSB chair Klaas Knot, will probably be revamped.

The critical point : Liquidity, I write your name

Liquidity is indeed a game changer when assessing banks’ solvency and sound standing. Looking at recent academic literature on the topic, a timely article published in May 2023, by Julien Dhimma and Catherine Bruneau, titled « The impact of specific liquidity shocks on the bank’s solvency », explores the relationships between episodes of liquidity stress and the solvency of a bank.

The article distinguishes itself in the literature by putting the liquidity shock as a root cause for a spiraling circle that leads a bank to insolvency. In fact, in a similar turn of events of that of the 2023 banking crisis, the model presented in the article describes how a liquidity shock, possibly unrelated to the bank’s initial solvency situation, can lead to capital losses, through the sale of illiquid assets at depreciated value due to liquidty shortages. These losses can be further aggravated as they cause second round effects, since they fuel the outflow of funds and reduce the bank’s access to market refinancing. These protracted losses lead the bank’s assets value to fall below the default threshold, i.e. a depreciation beyond the disposable capital to cover the balance sheet mismatch.

Numerical application to the model, with a set of pre-established hypotheses, shows that the highest the share of liquid assets, the lesser the probability of default of the bank, either subsequent to the first initial liquidity shock, or to the second round effects. Other articles from the literature, e.g. , “Interactions of bank capital and liquidity standards within the Basel 3 framework: A littérature review”, from Clerc et al., in 2022, identifies an easier and less costly access to liquidity for the most well-capitalized banks, translating a high level of confidence from creditors.

These findings plead for more entrenched linkages between liquidity standards and capital adequacy requirements. Additionnally, the aftermath of the 2023 banking crisis revealed some weak spots in the current liquidity standards, notably on what relates to :

- the speed and magnitude of bank runs : in the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) framework, monthly withdrawal rates for sight deposits are set between 3% and 15% for the bulk of depositors, retail and corporates. Those regulatory rates proved totally irrelevant during the crisis of 2023. In a single day, March 18th, Crédit Suisse witnessed the withdrawal of 16% of its sight deposits, which recalls the words of Joseph Stiglitz commenting the latest banking turmoil episode : « They used to think that bank accounts were sticky. But if everybody has internet banking, it’s much easier to take your money out and put it somewhere else. The question about the stability of the financial system has to be rethought, recognising the new technologies.«

- the liquidity of sovereign bonds/treasuries : another flaw in the LCR framework is the treatment of sovereign bonds and treasuries. Currently, along with cash and central bank deposits, they figure in the level 1 of liquid assets, which accounts for 60% of total liquid assets and suffer no haircut of their market value. This is not consistent with reality of 2023 environment of a return to high interest rates that depreciates the value of pre-existent bonds of all sorts, including sovereign ones.

Moreover, liquidity woes prompt shortcomings in other areas of risk management, namely interest rate risk management, where current Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book (IRRBB) framework is being recalibrated in terms of shock parameters to re-adapt to the high rate environment, but still is part of Pillar II, which induces a lot of discretion to supervisors in its monitoring.

Another affected area is accounting, though this time it only concerns the US, and it concerns the distinction made between Available For Sale (AFS) and Hold To Maturity (HTM) assets, which allows banks to book the assets falling under the second category with their initial purchase/origination value and is of nature of blurring the market participants over the financial soundness of banks, especially when comparing it with the Mark-to-Market (MTM) or Fair Value standards in other jurisdictions.

Finally, the 2023 banking crisis is also an opportunity to reassess the fitness of the insurance deposit schemes, in light of the new technological and macroeconomic realities.

Sources of danger : Regulatory pace, scope of application and the monetary policy cycle

Though relatively fast and swift in some regions, the application of BCBS frameworks can take time. New regulations must be translated in domestic law and legislators and regulators generally favor phased approaches to allow the industry to cope with sometimes lenghty and tedious transformation processes. According to an FT article, the 2017 Basel package is delayed in most jurisdictions until 2025.

Whatever might be the importance of regulatory changes subsequent to the 2023 banking crisis, chances are that they might not be equally applicable to all banks, depending on local regulators and supervisors arbitrages. The 2023 crisis, especially in the US, is the blatant example of the discretion a regulator might demonstrate in the oversight of some banks in relation with their size or the nature of their activities, and the risks such discretion entails.

Last but not least, many renowned observers, and at their front, Raghuram Rajan, former governor of the Reserve Bank of India, are raising their voices to warn about the risks the current monetary cycle represents for financial stability. In Rajan’s views, past ultra-accomodative monetary policies created massive risk-taking incentives for banks, as evidenced by this quote of SVB’s CEO, Greg Becker : « Indeed, between the start of 2020 and the end of 2021, banks collectively purchased nearly $2.3 trillion of investment securities in this low-yield environment created by the Federal Reserve.« . The Fed was also blamed for bad signalling, as it held for quite some time to a discourse of « transitory » inflation.

It is no suprise that SVB’s CEO puts the blame on systemic causes, however, one cannot ignore those factors. Researchers who analyzed banking crises in 17 countries over 150 years came to the conclusion that crises are typically preceded by a U-shaped interest rate path, signalling that periods of easy money tend to encourage risk-taking behaviors that are sanctioned by the markets in the interest rate steepening phase.

These patterns questions the neutrality of monetary policy with regard to financial stability issues. In fact, policy rate setters are facing today a conundrum : if they raise rates to quickly, it might provoke a disproportionate rise of banks’ cost of funding, and, if, on the other hand, they leave inflation unchained, long-term rates will increase causing a reduction of bank assets’ value.

In sum, today’s banking sector stability and landscape are highly nuanced, with both reassuring and worrying factors. The equilibrium is fragile and policymakers ought to be highly cautious in their decision-making processes, ensuring both short term and long term measures are appropriately designed.

In financial stability as much as in monetary policy matters, we are navigating today in uncharted waters. For better and for worse.

Laisser un commentaire